Last semester at FernUni Hagen was all about Großstadtliteratur (urban literature? Metropolitan literature? Eh, books about big city life. You get it.) and provided me with a huge collection of extracts and excerpts from the finest authors from the turn of the 19th/20th century.

I’ve read some Rilke and some Raabe, the whole fivehundredsomething pages of Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, and travelled abroad to Joyce’s Dublin and dos Passos’ Manhattan. My journey began in 1482, Paris, with Victor Hugo and his Nôtre-Dame de Paris (1831). A true classic and yet: So. Overrated. Maybe it gets better once the prominent Quasimodo plot unfolds. But the first couple of pages are merely a tedious and very detailed description of the geometrical patterns, the metropolitan maze and the architectural composition of Paris. It’s not just a literary travel guide, it’s the narrated Paris of Google Maps through the centuries and in 3-D-Zoom-In. Veeeery long. Once you think you made it through, a new paragraph starts something like “knowing this has all been a lot of information let’s try and summarize it all again” and then the narrator blabbers on for another 4 pages repeating everything he just said!! So not too keen on that one. The excerpt stopped here, so I wanna emphasise that it might get better. However, you shouldn’t judge a book by his cover (yet I do) but I think it’s perfectly acceptable to judge it by its first ten pages so my verdict is: boooooring!

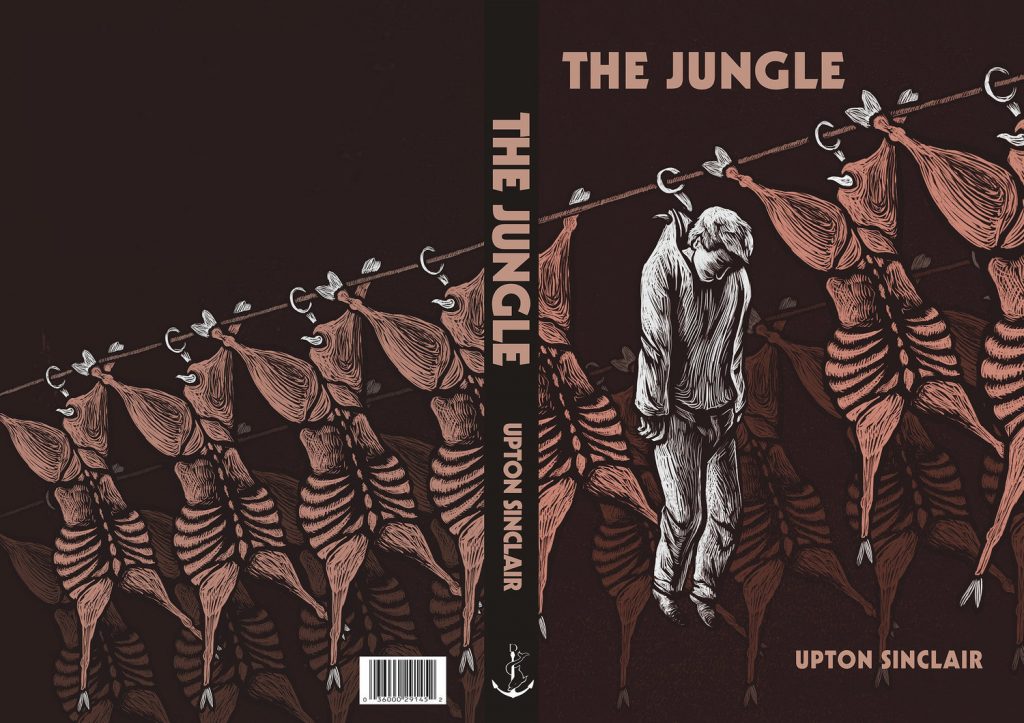

However, one book really stood out: Upton Sinclair and his 1906 novel The Jungle. There were only very few and very short excerpts but those very intriguing. So despite having already bought 5 post-exam-reward books, I decided I deserve the full story. And so I made opportunistic use of my American friends and now have my very own copy from a US secondhand bookstore and greedily devoured the whole thing within days.

Sinclair’s The Jungle is a ruthless account of the appalling labour conditions in Chicago’s meat (packing) industry and circles around Jurgis Rudkus, a Lithuanian immigrant, and his family, who were hoping for a better life and saw their American Dream shattered by corruption, greed and social brutality. It’s a pitiless urban jungle of injustice where the insignificant folks are doomed to become collateral damage of capitalism, a dystopian and sadly too real depiction of the exploitation of men and meat.

It was all so very businesslike that one watched it fascinated. It was pork-making by machinery, pork-making by applied mathematics. And yet somehow the most matter-of-fact person could not help thinking of the hogs; they were so innocent, they came so very trustingly; and they were so very human in their protests – and so perfectly within their rights!

[Upton Sinclair: The Jungle]

It is a sight to behold when a work of fiction has such effect on reality, i.e. the political world. President Roosevelt was highly appalled by the lack of hygiene and health regulations within the food industry displayed in the novel. Subsequently, the Pure Food and Drug Act from 1906 was passed to improve hygiene standards in meat production. Unfortunately, no such act was passed to protect the workers’ lives. Sinclair’s criticism with the working conditions were me(a)t with scepticism and considered mostly fiction. Needless to say, our socialist author was not happy with the outcome of his novel: “I aimed at the public’s heart and by accident I hit it in the stomach”, he once famously proclaimed.

Nonetheless, it had great impact and it’s social effects should not be diminished. Nor should its literary value. Before you stop reading here and start reading there: Be warned. The Jungle is a very intense narration that doesn’t spare your feelings. It is brutally honest. It’s depressing to read and on occasion makes your stomach turn. You just wanna rebel against greedy bosses, cheating estate agents, against the whole financial, social and political system. A system in which a Lithuanian family has to sacrifice everything they have in order to survive and yet, [SPOILER ALERT] it’s all in vain. Like a Gerhard Hauptmann novel. Bad in the beginning, worse in the end. How they try to hold on to their believes, traditions and each other against all calamities is heartbreaking. And calamities is a quite euphemistic word for jail, rape, death, and the likes. How the Rudkuses still manage to savour rare moments of happiness, culture and family makes it even worse.

To do that would mean, not merely to be defeated, but to acknowledge defeat – and the difference between these two things is what keeps the world going.

Upton Sinclair: The Jungle

Despite the family’s harsh fate, Sinclair ends his book on an uplifting note and offers a way out: socialism! Introduced to Jurgis (and us) towards the end of the book, it equips the working poor with a new hope, a vision, something they can hold on to and believe in. Socialism as the solution to capitalism is the clear message Sinclair wants us to tske from this book. In the 27 preceding chapters, he relentlessly and vividly depicts capitalism as the source of all evil. By narrating the sad and horrible fate of Jurgis and his family he easily plays our heart strings and sense of justice. You can’t but abhor a system that allows such tragedy to happen. In the end, The Jungle is superb socialist propaganda through the gut-wrenching tale of one immigration family. And a must read, political stance aside.