Mikhail Bulgakov, THE HEART OF A DOG, Harvill Press, 1999

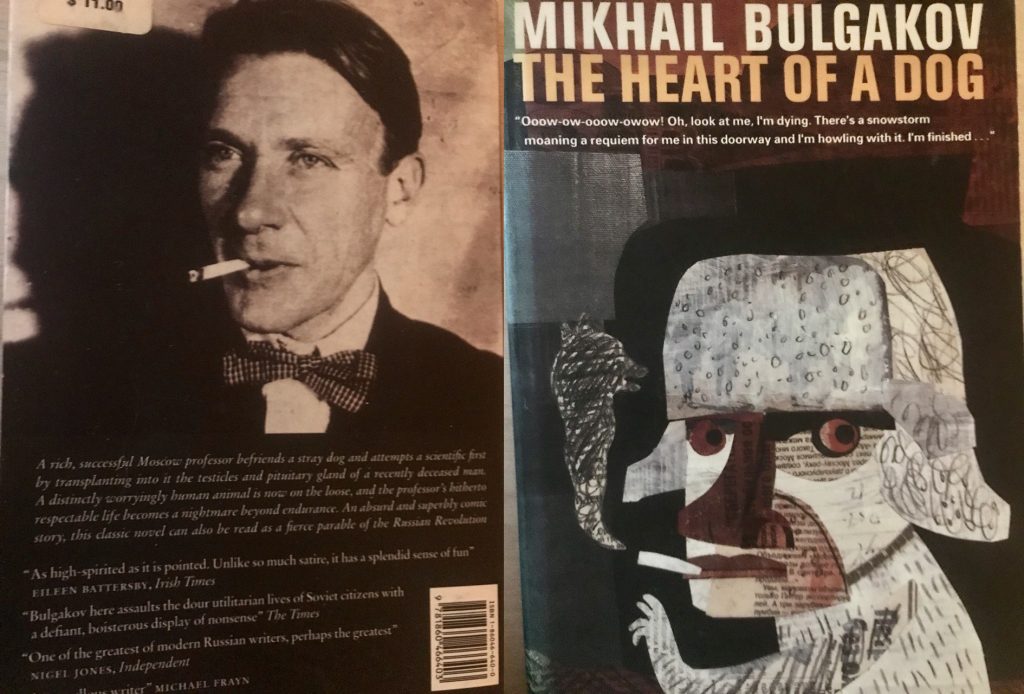

I stumbled upon this beautiful edition outside an antique book store right across the street from the theatre and simply had to buy it. Look at the cover and the author-protagonist-correlation! To all the Nepper, Schlepper and Bauernfänger out there: I can easily be fooled into buying a book. Just make it look tempting. I’m a victim to artsy editions. The aesthetics of a book matter as much to me as the content. Naturally, this gem joined my comprehensive collection. Собачье сердце was written in 1925, in the aftermath of Lenin’s death and at the height of the NEP (a market-oriented economy policy and one of many revoultionary developments from Russian Empire to communist state. Imho, the Soviet Union is one of the most fascinating chapters in modern history. I recommend the introductory works by Jörg Baberowski, a historian specialised on the Soviet Union and the Stalinistic Terror. Fairly comprehensible to read, too.). The novella wasn’t (allowed to be) published until 42 years later, in 1987 – the year many great things saw the light of day. Me, for instance. But back to Bulgakov and 1925. His Twenties are not roaring, they are howling and barking and generally fairly miserable. At least Sharik, our furry protagonist is:

Oooow-ow-ooow-owowo! Oh, look at me, I’m dying. There’s a snowstorm moaning a requiem for me in this doorway and I’m howling with it. I’m finished…

(first sentence)

Drama queen much?

In the cold, cold winter night our story unfolds, professor Philip Philipovich – mind you, not a comrade, but a citizen, a gentleman even, a dog can smell that! – is also roaming the streets of Moscow and in the snowstorm’s whirlwind their paths cross and events take an unexpected turn for Sharik. For the better, it seems. Triggered, tempted and lured by a irresistebly deliciously smelling sausage, Sharik willingly follows him into his home, “absorbed by a single thought: how to avoid losing sight of this miraculous fur-coated vision in the hurly-burly of the storm and how to show him his love and devotion.” Life in Philip Philipovitch’s 7-room-apartment (7 rooms for 1 comrade – what an outrage for his Bolshevistic neighbours!) is quite the opposite of the proverbial dog’s life , and soon his mood shifts from despair to high self-esteem, pride, and a good deal of arrogance. It doesn’t take long and Sharik behaves like he owns the place and deserves this wonderful new life of his:

Perhaps I’m good looking! What luck.

Damn, I wish I had that self-esteem.

[I gotta interrupt here for a very meta event. It’s 5am on a Friday morning and I’m watching Pointless on YouTube (skip to 28:07) while writing this and the categorie that comes up the second I start writing about a fictional dog is FICTIONAL DOGS. So meta.]

[MIKHAIL BULGAKOV, THE HEART OF THE DOG ]

Of course, Philip Philipovitch really did pick up any stray mongrel and not the long lost dog of the tsar family and not as a random act of kindness either (sorry to break it to you, dog pal). Comrades and Comradesses: meet professor Philip Philipovitch, expert for rejuvenation and on the quest to unravel the secret of eternal youth. Sharik is his latest (or from where we currently find ourselves in my plot synopsys more precisely his next) project and will soon experience drastic change in life. An interspecies operation is about to happen! Frankendog or The Soviet Prometheus you might call it. And don’t give me that “it’s actually Frankenstein’s monster, not Frankenstein” speech, because if you actually read the book you’d know that Frankenstein is indeed more monster than the monster… Back to Philip Philipovitch’s laboratory. Halfway through the book, after nursing and caressing Pooka Sharik to live up to his name (that translates as “little ball”), a fresh dead body, formerly known as Elim Grigorievich Chugunkin, 25, unmarried, sympathetic to the Party, plays the balalaika in bars, poor physical shape, enlarged liver (alcohol) is delivered to Philip Philipovitches door, ready to have his testicles and pituary gland removed and transplanted into a heavily sedated dog. For those who are as ignorant as me when it comes to the pink walnut in our head: that’s the part responsible for releasing hormones. Bulgakov was a medical doctor, so he knows what he’s talking about. Bulgakov was also an excellent writer, in case you hadn’t noticed. Ooow-ooow, I could I’d just copy and paste the whole text because there are so many mentionable sentences! But then you’d miss my wonderful comments on it and it’s too nice a book to own to read it online (and reading online is tedious unless its my blog of course) so I’ll go with an unusualy high percentage of quotes that is so out of proportion, if this was a term paper for a literature class, I’d fail it. The narrative perspective switches back and forth between an omniscient commentator, scientific observation protocols, and personal dog’s point of view which is a hilarious technique and adds to the general grotesque, brutal and brilliant deadpan humour consised onto 128 highly entertaining pages.

And now meet and greet the one and only, the hybrid, the medical miracle, the latest craziest creature in creation: Poligraph Poligraphovic Sharikov. Half-human, half-dog and not a pleasant company. He walks and talks – and sometimes the man barks indignantly – but really, he swaggers and swears. He’s an alcoholic bully with basic education and a weakness for chasing cats.

Sharik can read. He can read (three exclamation marks).

He’s the perfect allegory for the foredoomed dream of the the Soviet Übermensch, a Bolshevistic satire, a proletarian joke, a ridicule of the Russian Revolution. Needless to say, Philip Philipovitch is not amused by the outcome of this and the plot denses towards a drastic solution against the drunken bully without manners or etiquette. Philip Philipovitch aimed for Brian Griffith and got the fucked-up black sheep dog of the family instead. The Heart of the Dog is hilarious, on point and dead funny. Phantastic and preposterous.

And if it wasn’t for some old groaner singing ‘O celeste Aida‘ out in the moonlight till it makes you sick, the place would be perfect.